Since Trump was re-elected, the analysis on the liberal-left has turned to what went wrong. It is always, of course, the economy, stupid. No incumbent performs well during inflationary periods. However, reducing everything to economics forgets that the economy is one thing, but economic discourse is another. The latter is informed by culture, vocabulary, the wider language and assumptions of economics, plus how that discourse is connected to other spheres of political, social, and cultural life. This economic discourse sits up against other discourses - rights, foreign policy, ‘wokeism’, gender relations, race, identity, the deep state, big tech - take your pick. In fact, you can even pick ‘n mix: DEI slows the economy? China wants on a weak divided U.S? The ‘Woke Mind Virus’ (cough) has captured institutions? The polycrisis, to use Edgar Morin’s phrase, is complex.

So saying it’s all about the economy can be reductive. But there’s another reductive lens that I think is useful and increasingly influential: The populist one.

The literature on modern populism is vast - ranging from the nineteenth century Farmer’s movement in America over to the Russian anti-tsarist Narodniks, through to postwar Populism. So is the debate on the similarities and differences between Populism and Fascism.

But it’s also reasonably simple; Much of our current political moment can be analysed through the populist lens of ‘ordinary people’ vs ‘elites’.

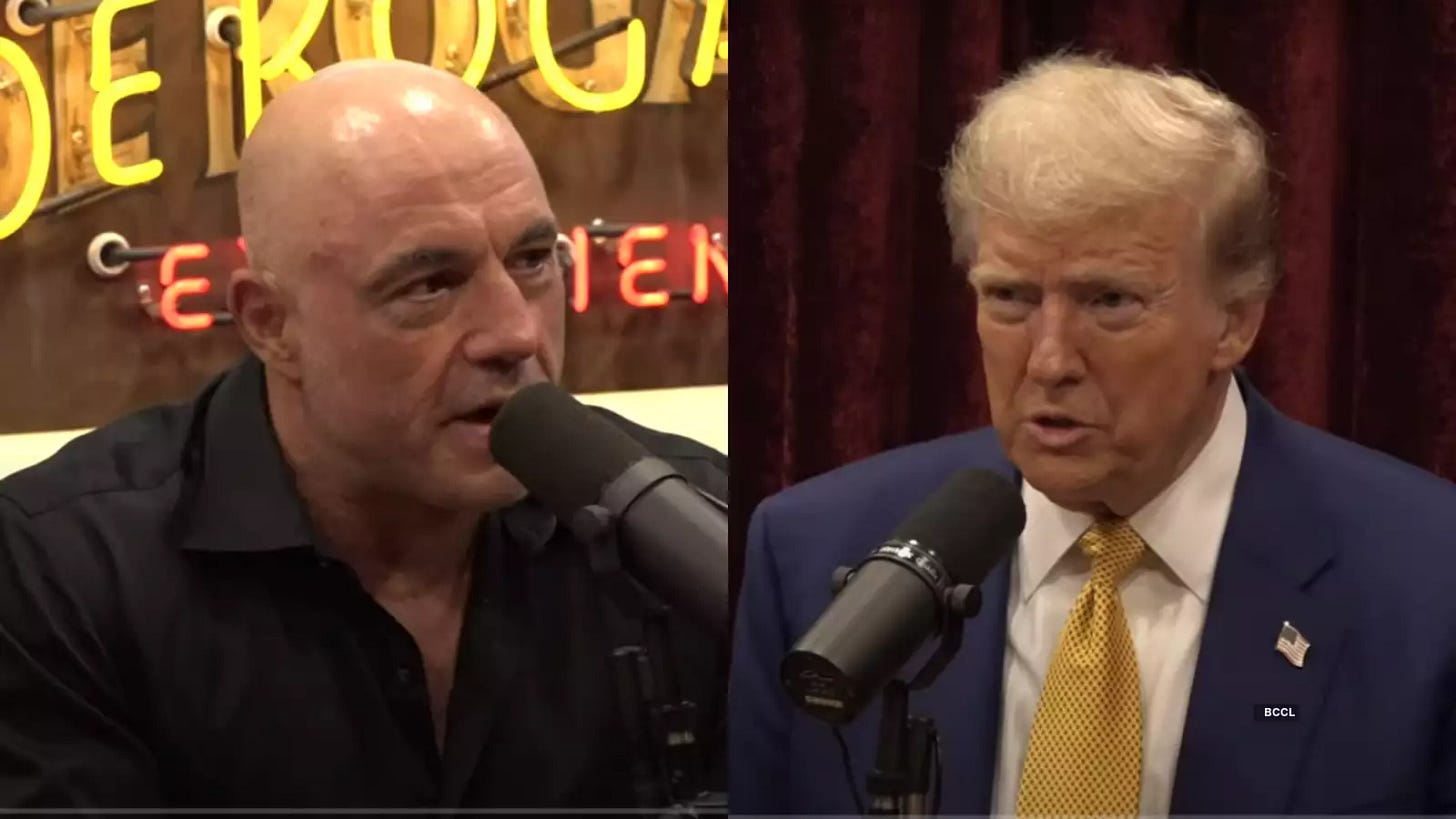

Take the so-called Joe Rogan Effect. The podcaster’s interview with Trump clocked up some fifty million views on Youtube alone. While Spotify and Apple don’t release their figures, it’s a fair estimate that most of America at least knew of the conversation. This is only the most obvious example of Trump’s numerous other appearances in the Rogansphere; on Theo Von, Andrew Shultz, Lex Friedman, etc. Not to mention his connection to Musk and Peterson - all of whom have been derided by many on the left as being the spokespeople for disaffected ‘ordinary’ young men.

In the aftermath of the election, the idea that liberals need a Rogan of their own became controversial enough to trend on X. Many pointed out that Rogan himself wasn’t inherently conservative, and had supported policies (UBI) and people (Bernie Sanders) firmly on the left.

I think all of this misses a few fundamental points about the Rogansphere. First, it is not an inherently or exclusively political machine in the same way the Republican Party or MSNBC or Tucker Carlson is. Instead, these podcasts are a social and cultural machine that are, more than anything, positioned as a new media format representing new fractured media technologies. They are an alternative to old establishment media in a period of discontent. They are, then, almost inherently anti-establishment.

In fact, these contrarian impulses are the kind of cultural anti-establishment forces that most ‘ordinary’ people instinctively know quite well. ‘Ordinary’ people don’t care about politics. ‘Ordinary’ people know little about it, they don’t have the time, (although more than they did one hundred years ago), and it takes up a small part of their lives. More than anything, ‘ordinary’ people despise politicians; they suspect corruption, greed, and incompetency behind all closed doors; raging against the machine comes naturally to them; and they see WASPS and Londoners and metropolitan elites as being fundamentally different from themselves.

This has always been the case, but the intensity of this impulse becomes more potent whenever things are - or are perceived to be - going awry. Clearly, since 9/11, through to the 2008 crash, into the pandemic, and through to high inflation, anyone who is meant to be managing the recurring shitshow is unlikely to be seen in a favourable light.

The internet has added an extra dimension to this. Increasingly, each online talking point - Gamergate, conspiracy theories like Pizzagate, the emergence of Jordan Peterson, the realignment of Russell Brand, the mainstreaming of the ‘Manosphere’ and terms like ‘NPC and the ‘Matrix’ as slang for ideological-captured-non-thinking people - all have this anti-establishment drive and vocabulary at their core.

I’ve talked about how the new internet elites - Rogan, Triggernometry, Musk, Peterson, etc - are driven by a constellation of ideas revolving around this populism. I believe that video holds up well in light of the election, although none of it was particularly controversial. The central thesis wa that new media podcasts and Youtube channels are incentivised to become populist as they are instinctively antagonistic to mainstream media and adjacent institutions, and so, importantly is the average ‘ordinary’ viewer. All incentives - ideological, analytical, in-group dynamics, likes, shares, ad revenue - can quite easily push you in that direction. Over and over, new elite figures claim to be ideologically free while parroting the same ideological lines their podcasting compatriots squawk too: That elite woke institutions want to control you, tell you what to think, when to think it, who you can say it to, and when you can be stopped.

As I’ll get to, they have a point. But they almost invariably, because of the incentives, take this populist energy firmly to the right - critiquing almost every institution, from the media to education departments to regulatory bodies, except the institution of the corporation (Big Pharma and Big Tech are the occasional exception to this, but for social or cultural reasons, I’d argue, rather than economic ones). Rogan’s shift from Bernie Bro to passionate Trump advocate is case in point. I don’t think it’s opportunistic, his sphere of influence provides so many incentives to push a person in that direction, that, unless you have a strong set of political beliefs (which, again, most people don’t) your only guide are those incentives.

I don’t think the Left can ignore all of this. The Left should thoughtfully draw on this latent populist energy because, unfortunately, it’s populist vibes that matter. This was an election in which policy hardly seemed to feature at all. Trump’s flagship tariffs have been roundly rejected by economists as being unlikely to achieve what he wants and to likely drive inflation even higher. No-one really cares (for now). Politicians selling policy is like a car salesman selling a car; no-one is that interested in how the engine works, only that it makes a nice sound and looks shiny. Voters are much more interested in the look and feel of a policy. They’ll decide whether it’s worked or not if they kick you out in the next election.

Trump’s policy then aligns nicely with the exterior vibe of a popular American truck’s metalwork. It is muscular against China, bold and fast with aspirational American values, and anti-woke towards an establishment deemed as being controlling, bureaucratic, obsessed with identity, effeminate, and intent on telling you what to think. Rightly or wrongly, the Left lost, at least in a large part, on this ground.

‘Ordinary’ people want a shake up; they want to feel like their interests are not just represented, but that they’re part of the political game they’ve for so long had no interest in. Trump’s rally’s, social media’s political turn, and the rise of political podcasts are popular for this reason. While it’s still true that most people are not interested, it seems (and maybe I’m in a bubble here) the number that are is growing. We are, as Aristotle noted, political animals. When it’s their lives, people want to participate and feel like they have agency. But the image the liberal-left present is business as usual, institutions are fine, we know what’s best, we don’t even need a democratic primary to pick a candidate.

In her 2018 For a Left Populism, the political theorist Chantel Mouffe argued that the Left needs to embrace these populist ‘ordinary people’ vs the ‘oligarchy’ impulses. Mouffe wrote that ‘a left populist strategy cannot ignore the strong libidinal investment at work in national – or regional – forms of identification and it would be very risky to abandon this terrain to right-wing populism.’

The elite left (and this is especially true in Britain) often fears heartland politics and national identity. It believes that anything nationalistic (even the Union Jack) either whiffs of colonialism, or is somehow the exclusive purview of white football hooligans and pot-bellied louts. That anyone north of SW1 or south of Washington is, in Hillary Clinton’s famous gaffe, part of the ‘basket of deplorables'.

But the nation - it’s culture, language, pastimes, humour, etc - from flag to sports to food - is the unignorable starting place of all politics, downstream as politics is from culture. As Mouffe points out, ‘the hegemonic struggle to recover democracy needs to start at the level of the nation state that, despite having lost many of its prerogatives, is still one of the crucial spaces for the exercise of democracy and popular sovereignty’.

In short, if much of the current political discontent is levelled towards inequality, international bankers and their bonuses, multinational corporations, tax-avoidance, and deficits, then the sovereignty of the ‘people’ in a ‘nation’ is one of the most effective, if not the only effective, platforms for resistance. It is only through national democracy that institutions - even global ones - can be reformed.

The right uses the populist impulse to attack every institution, but we need institutions in all their forms - from good media to good schools. We need good regulation to protect us, good medical research, the organisational and budgetary capacity to get reporters to a warzone or to attract, train, and retain good school teachers. We need strong dynamic institutions to keep other institutions in check when they go wrong. But we also need institutions that grow, reform, and change with the times. The Right’s impulse is to take a chainsaw to institutions, to use Javier Milei’s neoliberal phrase. The Left’s impulse should be, to state the obvious, progressive - to argue for radical reform. In other words, to be anti old establishment and pro new ones at the same time.

When Jeremy Clarkson was asked at a recent farmer’s march where the government should get money from for public services, he pointed ambiguously to the windows of the Civil Service in Whitehall and said ‘go into those offices and ask each person what their job is. If you can’t understand it, sack them.’

He has a point, just not the one he thinks. It’s not that the Civil Service doesn’t matter, it’s that to most people it’s an opaque machine behind London walls that is completely incomprehensible, representing the worst of national bureaucracy and middle-management. It’s the same reason that when Elon Musk talks about heading a Department of Government Efficiency to trim the trillions of dollars of fat from US debt, people listen.

The left used to know this. The anti-establishment sprit dominant since the 1960s consistently made the argument that the establishment had become a Kafkaesque machine. The Hippies led the rejection of ‘the man’, the suit, the square, the corporate shill. The left has abandoned this drive because of its fear of attacking the institutions that have in many ways enacted many of its demands - from civil rights to mental health care.

But it’s forgotten its own lesson: reform, radical change, new approaches are always needed. History doesn’t stand still. This is good rhetorical ground for the left. Institutions can be defended as necessary while acknowledging they need radically changing - made more accessible, more transparent, more dynamic, more democratic - in a new digital world. People’s relationship to information is shifting and so the structure of institutions must shift with it.

But this is also good practical ground for the left. The MAGA right in the US and its counterparts in Europe play a populist trick. They pretend to be a new type of outsider conservative. They say they’re there to ‘drain the swamp’ and to help ‘ordinary folks’ on the one hand, while pursuing the same libertarian-conservative, state shrinking, tax-cutting policies on the other. They may be less interested in foreign wars and keen to build walls, but on the economy and how it effects ‘ordinary people’ there’s no substantive change.

These new ‘champions of the working people’ pretend to be populist while increasing capital gains tax breaks. They claim to be doing something new while playing the same tired old game of trickle-down economics. They pretend Donald Trump and the Trump oligopoly, Elon Musk, Peter Theil, Dave Rubin and Jordan Peterson are not elites.

The reason they’re successful is that whether something like Trump’s tariffs are effective or not, Trump is at least responding to some of the issues of what has been called Post-Democracy, the idea that national democracy has become toothless in the face of global forces. These are the very issues that have mobilised populists since Occupy, 2008, Brexit, etc. That ‘ordinary’ people feel that democracy has become impotent, subservient to investment banks, corporate threats, backroom deals, and the realities of global supply chains.

All of this is obvious ground for the left, but it’s been ceded to the right because the left is largely unwilling to put up a populist fight because of it’s fear of undermining institutions that the right attack. The approach should instead be to attack, criticise, analyse, and radically reform.

Finally, there is another part of the populist drive that the left is not good with: aspiration. The Rogansphere responds to aspiration in a way the left often neglects, having a tendency to focus on welfare, social security, and nanny state policies at the expense of ‘ordinary’ hardworking aspirational values, promotions at work, housing ladders and support for small businesses. The left sometimes forgets that both are important, and the latter is especially important for having a strong economy that pays for the former.

Defending and strengthening both the aspirational dream and social security is obviously crucial. However, overvaluing the former at expense of the latter forgets that the ‘ordinary’ working class person isn’t helpless, desperate, or ill-educated. At any given moment, the percentage of people in need of state aid is small compared with the number that are working morning to night, struggling to get a promotion, or desperate to build a small business. In other words, helping people (small business tax breaks, grants, free courses on SME, etc) when they’re well and thriving should be as important as helping them when they’re not. This is where the median voter is.

Online populist spaces capture this aspirational energy well. Much better than the mainstream media ever did. Personal development, interest in philosophies like Stoicism or Existentialism, Peterson’s emphasising of purpose and responsibility. The left often disparages this ground instead of owning it. The case can quite easily be made that individual responsibility and personal success applies as much to contributing towards our institutions and communities as it does to ‘personal growth’. This ground in its current form is often left to personal growth meaning becoming David Goggins or starting a ‘side hustle’, rather than it meaning becoming a scientist, engineer, psychologist or any other profession that means going through an institution.

Mouffe’s wider point is that left populism should aim to ‘deepen and extend’ democracy. The core principle should be to increase self-determination, expand freedoms, broaden the ways people can control of their lives, feel connected to their communities and politics, their education, workplace, and health; to feel as if we are our institutions rather than them being some separate deep state alien entity.

Mouffe writes ‘A left populist approach should try to provide a different vocabulary in order to orientate those demands towards more egalitarian objectives.’

The point, then, is not to construct some alternative Rogansphere, as if half the population is beyond reaching and ‘ordinary’ people are automatons stuck in preconceived boxes like ‘disaffected young man’. It’s to build modes of thinking and communicating that connects with and unites as many ‘ordinary’ people as possible.

During the Enlightenment, the philosophes mostly argued that people should dare to think for themselves, instead of taking the word and orders of popes, priests, and seigneurs. Conservatives of the period believed that ordinary people were incapable of thinking for themselves, that the widening of the franchise would usher in the end of the civilization. Instead, the fourth estate expanded, political parties thrived, education was reformed, unions legalised, technology improved, publications flourished, women (eventually) went to work and to the polling booths… the list of democratic achievements goes on.

I think optimistically that we live in a comparable expensive moment. People increasingly want to think for themselves, read for themselves, understand the issues, and to expand the ways in which they can contribute to political and civil society. We need a politics that revolutionises the line between ordinary people and elite institutions. Like the Republic of Letters and newspapers of the Enlightenment, the internet has made civil society a much more powerful political force than it was in a more ‘elite managed’ past. Do we not now have the digital tools to revolutionise the relationship between representatives, constituents, institutions, the civil service, etc. To at least make them more transparent, more responsive, more dynamic? To allow ‘ordinary’ people to understand, feel connected to, and contribute to the systems that have power over their lives?

I’ve been sceptical of populism in the past. It has a chequered history, can be dangerous, and reductively simplifies who ‘ordinary people’ and the ‘the elites’ are, incentivising framings like ‘ordinary’ native vs immigrant or ‘pure Englishman’ vs corrupt globalist. But the populist impulse has some stand out moments too. The Farmers Movement in the US was a motivating force for the New Deal later on. The anti-tsarist Narodnik’s had good intentions.

But it’s even more dangerous ceding the populist drive to a populist right who are not as interested in ‘ordinary’ people as they often claim. The Left shouldn’t ignore a weapon because it’s dangerous, it should pick up the weapon before the enemy does and use it responsibly.

Lewis Waller with a Substack? Yes please. Love your videos.

Finally. Glad you’re here!